Brandon Elementary was recognized nationally as an extraordinary school. Here’s why.

Nov. 23, 2021

Source: Mississippi Today

When Brandon Elementary School Principal Vallerie Lacey’s son was in the third grade, something happened that changed her as both a parent and an educator.

That change would play a huge role in why Brandon Elementary was recognized as a national Blue Ribbon school for closing the achievement gap between groups of children who historically underperform their peers.

The U.S. Department of Education’s National Blue Ribbon Schools Program recognizes extraordinary schools in two separate categories: overall academic excellence and progress in closing achievement gaps among student subgroups. This year, 325 schools received the honor nationwide. Brandon Elementary School in Rankin County School District, along with Woolmarket Elementary School in Harrison County School District, received the distinction for having the highest rates of closing achievement gaps among their students over a three-year period.

East Hancock Elementary School in Hancock County School District and Della Davidson Elementary School in the Oxford School District were recognized for their students’ overall academic performance.

The achievement gap is calculated by comparing the proficiency levels of certain reference groups (students who are white, do not have disabilities, are not economically disadvantaged and speak English as their first language) on state tests with other groups, including English learners, students with disabilities, and African-American and Hispanic students.

What this school has done is no small feat — statewide, the gaps between all but one of these subgroups have widened over time. At Brandon Elementary School, the proficiency gap between economically disadvantaged students and their more affluent peers decreased in both English Language Arts and mathematics from 2017 compared to 2019. The gap also decreased in both subjects between students with disabilities and those without disabilities, in addition to Black students compared to white students.

There was around a 30% gap in proficiency in both mathematics and English Language Arts between Black and white students in 2019. There are also similarly wide gaps between economically disadvantaged students and their more affluent peers in both math and English, in addition to students with disabilities and those without.

These gaps only widened in the spring of 2021 as a result of the pandemic.

Lacey attributes these gaps closing at Brandon Elementary as a direct outcome of her vision and mission: inclusion. In education lingo that refers mostly to students with disabilities, but she and the staff at Brandon apply it to everything.

When Lacey was an assistant principal at Florence Elementary, her son also attended school there.

“When he was in third grade, a team of educators came and sat me down and told me my baby was autistic,” she remembered. “It was the first time I’d ever heard it, and it completely changed my life in that moment as an educator and as a parent.”

He was given a special education ruling and received an individualized education plan (IEP), or a written document that includes annual goals, special services, any needed testing modifications and how the student’s progress will be measured, among other items. He was routinely removed from his general classrooms to receive services from a special education teacher.

Until one of his teachers came to Lacey with a concern.

“She said, ‘When he gets pulled out of the classroom, he’s missing instruction. I need him not to be pulled out of my classroom,’” Lacey recalled. She went to his special education teacher and they made some adjustments to his plan.

“That was the only year of my son’s whole academic career that he was not minimal on state achievement tests … all because there was a teacher caring enough about my kid to say, ‘Don’t let him be pulled out of the room,’” she said. “It changed my whole mindset.”

Since then, Lacey has emphasized inclusion in every sense of the word. It’s what she was determined to instill in the culture when she came to Brandon Elementary in 2018.

Whenever someone has an idea for a club or an event, her first question is always the same: Is it inclusive or exclusive?

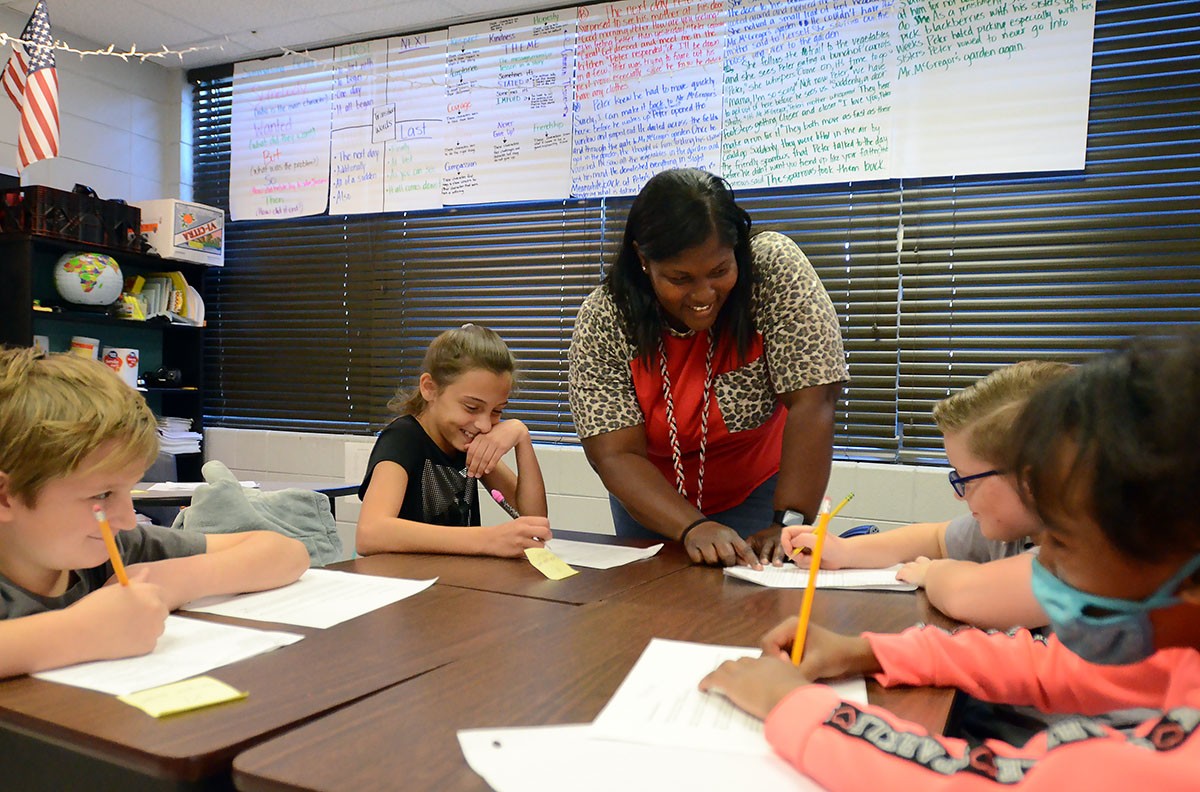

The term “inclusion” even applies to the way the teachers teach. Special education teachers work alongside other teachers in the classroom, similar to co-teaching. The teachers say students don’t view them as general and special education teachers, and they will often alternate teaching lessons to the whole class.

“It’s really easy when you have a student who comes in with an IEP … to look at that label and say ‘Oh, they’re not going to be able to do what everybody else can do,’” said Jeremy Cooper, a fifth grade special education inclusion teacher. “Whereas we start with trying to get them to do what everybody else is doing first. We hold them up to a standard of rigor and of excellence because we want just as much for them as we want for our other students.”

She and the other teachers also make a concerted effort to know every individual child — both academically and personally.

Despite the fact there are around 800 students who attend the school, she and a team of teachers, guidance counselors and an interventionist meet monthly to discuss every individual student in depth. If the student is not growing, Lacey and other teachers say, the conclusion is not that the student can’t. The conclusion is they need to try something different to help the child grow.

And they know more about the students than just their academics.

“I can tell you what kind of car people drive because I stand outside every morning and wave goodbye every afternoon. If I don’t do anything else, I’m intentional about saying good morning and goodbye every single day, rain, snow, sleet or shine,” she said. “I do it because you can tell a lot about how a child comes in, how they get out of the car, their body language.”

Susie Dill, an interventionist for the school who helps identify students who may need special services, echoed Lacey. She said teachers make an effort to know everything they can about each student who walks in the doors.

And recognizing the importance for students to have teachers they can relate to outside of academics, Lacey prioritizes diversity when recruiting and hiring teachers.

Students who may be struggling with issues at home often have weekly check-ins with teachers to whom they can relate. It’s part of a larger school and district-wide initiative to focus on the social and emotional aspects of a student’s well-being, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when students’ lives have been disrupted, they or their caregivers have gotten sick or, even died.

“As a result of COVID-19, we have had to take an even deeper look at students’ social and emotional health … We are more intentional than ever with incorporating social and emotional health into our target zone,” said Lacey, who mentioned the school, along with the district, is reading Jimmy Casas’ “Culturize,” a book about instilling values such as kindness, honesty and compassion in students while challenging them academically.

“While we are still very committed to continuing our charge in closing achievement gaps … we are more intentional than ever with incorporating social and emotional health into our target zone,” said Lacey.

ADD PAGE

As you navigate our website, you can use the “Add Page to Report” button to add any page or property to a custom report that you can print out or save.